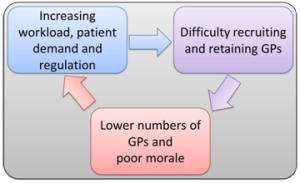

There can be no doubt that the problems facing general practice are complex and interconnected, and that the answers have proved elusive for many. GPs and the organisations that represent them have been very vocal about the obstacles hampering the ability of grassroots GPs to do their jobs safely and effectively: from increasing workload from hospitals (due to increasing patient expectations and demands) to the strain of excessive regulation. These problems and, some would argue, the way that they are discussed openly are probably contributing to the decreased recruitment and retention of GPs.

There can be no doubt that the problems facing general practice are complex and interconnected, and that the answers have proved elusive for many. GPs and the organisations that represent them have been very vocal about the obstacles hampering the ability of grassroots GPs to do their jobs safely and effectively: from increasing workload from hospitals (due to increasing patient expectations and demands) to the strain of excessive regulation. These problems and, some would argue, the way that they are discussed openly are probably contributing to the decreased recruitment and retention of GPs.

In fact, some have gone so far as to say that the difficulty of holding onto and training new GPs is because of existing GPs moaning about their conditions of work. It is a chicken and egg situation. They would argue that GP recruitment would be easier if all the problems of general practice were not discussed and bemoaned so openly. Well that may work for recruitment, temporarily, but GPs on the ground know how hard they work and what the issues are. They don’t need bloggers and social media to tell them that they are working harder than ever, often for less reward in real terms.

The dichotomy is that part of the solution to addressing workload issues is to ensure that recruitment and retention don’t lag below the required levels to maintain an effective workforce. A vicious cycle has been created that will be difficult to break. I don’t believe that launching a recruitment drive without addressing some of the core problems will be an effective long term solution.

The dichotomy is that part of the solution to addressing workload issues is to ensure that recruitment and retention don’t lag below the required levels to maintain an effective workforce. A vicious cycle has been created that will be difficult to break. I don’t believe that launching a recruitment drive without addressing some of the core problems will be an effective long term solution.

In my mind there can be only two possible solutions, neither of which is easy. The first overall strategy would be a concerted effort from NHS England and clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) to address the problems that are leading to this pressure in general practice. Part of this includes investing in general practice to make it a financially attractive option for bright young medical students and junior doctors. In addition, steps should be taken to ensure that GPs’ increasing workload, which has arisen from the shift in care from hospital to community, is followed by commensurate funding or reversed. A cultural change away from over-regulation would also help to ease the burden on GPs working at their limit.

By doing these things, GPs may be encouraged to work more sessions and increase their availability to patients. Most GPs will tell you that the part of the job they enjoy the most is the patient contact. Managing patient demand is a political hot potato that is unlikely to ever be tackled by the government or any of its appointed bodies. Doing so, however, could help ease the pressure on general practice.

I would question whether GPs in isolation, or even working together, can effect a countrywide change to the current situation; certainly not when there appears to be no limit to workload, patient demand, and regulation. However, we are our own worst enemies in that general practice continues to function despite the above problems. We adapt and stretch, adapt and stretch some more. Here and there practices reach breaking point and hand back their contracts, but life carries on, because we carry on. If the whole system was to collapse, perhaps that would provide the impetus for wholesale change. The status quo will not be overhauled until general practice stops working and secondary care has to pick up the pieces. In reality the only way that could happen in a controlled manner would be if industrial action via “work to rule” or mass undated resignations were to take place. One would hope that the unity displayed by the junior doctors could be replicated if it came to that.

Perhaps we need the threat of the second strategy to bring about the first. I worry that we will simply adapt and stretch, adapt and stretch, lose colleagues, and then adapt and stretch until general practice itself is distorted beyond what it should be.

Samir Dawlatly is a GP partner at Jiggins Lane Medical Centre. He is on the management board of Our Health Partnership and co-clinical director of QCAPS referral improvement scheme. All views expressed are his own. He can be found on Twitter as @sdawlatly.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: I am a member of the RCGP online working group on overdiagnosis.